Friday, February 29, 2008

Save Wolves from Federal Incompetence

The recent admission by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that only 29 gray wolves survive in Arizona (plus 23 in New Mexico) comes at the end of a multi-million dollar 10-year recovery effort. As a highly endangered species, our wolves, like all threatened animals in this great country, were afforded protection under the Endangered Species Act. But, instead of protecting the wolves as is their mandate, Fish and Wildlife continues to trap and kill the last remaining wolves in the Southwest.

Rather than listing the wolf population as endangered, Fish and Wildlife has, through a bureaucratic loophole, listed our wolves as an "experimental population" in the wild. This wordplay allows the government to exterminate wolves that venture outside of arbitrary wilderness release areas, as long as "backup" wolves are bred in captivity. Instead of letting mother nature restore the wolf for free, we pay millions of dollars to breed, release, and then kill wolves in an absurd parody of nature.

A more cynical citizen might presume political malfeasance in creating a "recovery plan" that was designed to fail. But I prefer to give the benefit of the doubt to our hardworking elected officials and presume that this situation is simply the result of one hand not knowing what the other is doing. The sheer incompetence, not to mention futile waste of taxpayer dollars, of this "experiment" is outrageous...with such low population levels the Southwest's gray wolf is poised to slip through a bureaucratic loophole into oblivion. If we wish to allow the wolf to survive we cannot allow the continued incompetence of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Thursday, February 28, 2008

Dead Flowers and the Giant Juicer

As someone who's known the value of compost, I can appreciate the value of detritus in nature, especially in the desert where organic carbon is often the limiting factor in vegetative growth.

As someone who's known the value of compost, I can appreciate the value of detritus in nature, especially in the desert where organic carbon is often the limiting factor in vegetative growth.

Are plants worth more dead or alive? Where does all the detritus go? Why do some ecosystems produce more dead standing matter than others? What does this say about ecosystem health or productivity? To answer these and many other fascinating ecological conundrums, ecologists would like to measure and compare the efficiency of different systems. Efficiency is conceived as the ratio of production (new tissue) to biomass (existing tissue). But,

"...there is another way of looking at the figures of productivity in relation to biomass. This is to say that biomass as we define it is a quite unrealistic way of measuring the standing crop of a community. For example, is it justifiable to treat the dead wood and bark of a tree as if they were in any direct way causally determining the rate at which that tree makes new dry matter (or fixes energy?) Nearly all the differences in community productivity that we see between community types arise because we choose to define biomass in this way. It might be much more sensible to define biomass in terms of weight of living tissue (if we could find a way to measure it)." p.720 Ecology. Begon, Harper, and Townsend.

To better compare measures of productivity the authors want to separate structural and detritus from actual living tissue. I suggest using a Giant Juicer (GJ) to strain out all the structural fibers...of course, their proposal begs the question of what it means to be "living" versus nonliving, because to measure dry weight they would evaporate the juice, leaving, at the bare minimum, most of the intracellular structural components. Are proteins alive? Maybe they should just measure the weight of DNA and RNA?

Measuring an accurate ratio of production to biomass (P:B) is useful for figuring out all kinds of stuff, e.g. how ecological succession affects productivity and whether natives or invasives sequester more carbon (i.e. are more productive). NB: since cropland productivity has been measured at utilizing nearly 10% of the available solar flux it is certain that native flora are usually suboptimal. (Limiting nutrients are the cause of suboptimal production.) But that judgement of "suboptimal" might only point to a flaw in our measurements: perhaps a long-term measure of the sustainable productivity would yield different results (organic farming?)...or perhaps this simply reiterates the hope of the Panglossian Paradigm in ecology, that natural systems are somehow "better" than man-made systems. Indeed, this does appear to be part of the assumptions of Permaculture (taking natural ecosystems as the model for our own human habitats).

It does seem that most living organisms in natural ecosystems create more habitat for other organisms simply as a side-effect of building their own tissues (parasites, detrivores) and homes (e.g. burrows, beaver dams). Humans appear to be the glaring exception to this logic, in that we more frequently destroy habitat (antibiotics, monocultures, cities) than create it.

It does seem that most living organisms in natural ecosystems create more habitat for other organisms simply as a side-effect of building their own tissues (parasites, detrivores) and homes (e.g. burrows, beaver dams). Humans appear to be the glaring exception to this logic, in that we more frequently destroy habitat (antibiotics, monocultures, cities) than create it.

But all these speculations must remain entirely philosophical and equivocal until my Giant Juicer can provide quantitative certainty...

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

La Jencia Documentation

Although La Jencia watershed is subject to ephemeral flooding events, the creek itself is perennial from springs ~100m upstream of our jobsite to its confluence with the Rio Salado. There is ample evidence that this system has downcut substantially in recent years. In fact, current GoogleEarth satellite photos record a markedly different channel from the current one. The older channel was probably active within the last two years.

On the ground it is obvious that this new channel is 3-5 feet lower than the previous channel/floodplain.

Due to the lack of on-site building materials and other reasons, our project does not directly address the channelization and downcutting but instead attempts an oblique approach to these hydrogeomorphic issues; by suppling more vegetation to slow and absorb large flow events we can limit further erosion as well as build up biomaterial that could someday provide substrate to dam, sediment, and eventually reconnect La Jencia with its floodplain.

We planted ~700 cottonwood and a few thousand willow poles along both sides of the channel for approximately 1/2 kilometer above the road crossing. Light green along stream banks is willow, dark green denotes cottonwoods. This is a crude approximation to give some idea of the size and location of treated areas.

Click on the photo above to enlarge it enough to see numbers marking the location and direction of each of the post-planting photographs] that follow:

[photo #0]

[photo #0] [photo #1]

[photo #1] [#2]

[#2] [#3]

[#3] [#4]

[#4] [photo #5]

[photo #5] [#6]

[#6] [#7]

[#7] Farewell, La Jencia.

Farewell, La Jencia.

Monday, February 25, 2008

La Jencia Jobsite

La Jencia is still a working ranch, with only a few remaining cattle and horses,

La Jencia is still a working ranch, with only a few remaining cattle and horses, but the erosion on the uplands and within the La Jencia stream channel are unsustainable,

but the erosion on the uplands and within the La Jencia stream channel are unsustainable, so Forest Guardians Stream Team was called in to do mechanical removal,

so Forest Guardians Stream Team was called in to do mechanical removal, which is probably the most difficult,

which is probably the most difficult, but effective,

but effective, means of clearing invasive and restoring native vegetation.

means of clearing invasive and restoring native vegetation. We harvested cottonwood and willow poles

We harvested cottonwood and willow poles and drove down to the creek to plant them...

and drove down to the creek to plant them... (note the white mineral crust on the soil)

(note the white mineral crust on the soil)La Jencia Jobsite Documentation

Sunday, February 24, 2008

Ecological Drama in the Southwest

The Saharan desert, as evidenced by cave-paintings, was once a fertile grassland. The drama of ecological change is one of the greatest epics humans can imagine. We are so small and yet not insignificant: we have caused it and can cause it again. We can look at the Sahara and see how it is now: we can look at the Sahara and see how the American Southwest might be in the future. The BLM estimates that western rangeland soils have already lost one half of their organic carbon content; Arizona has less than a third of its organic soil remaining. When all of the soil is lost the land will no longer support life.

What is the cause of the desertification in an already-desert land? As long ago as 1938 Aldo Leopold wondered "whether semi-arid mountains can be grazed at all without ultimate deterioration. I know of no arid region which has ever survived grazing through long periods of time, although I have seen individual ranches which seemed to hold out for shorter periods. The trouble is that where water is unevenly distributed and feed varies in quality, grazing usually means overgrazing." The extent of the damage is far worse than when Leopold wondered, so much worse that the only wonder is that we allow it to continue.

It is a failure of memory that allows us to complacently watch our ecosystems dry out and turn to dust. That Tucson's rivers used to flow along tree-lined banks is recorded, but easily forgotten in the scorching heat, augmented by urban heat-island effects, of the Sonoran desert. In urban landscapes like L.A. the connection between man and the environment has been completely severed; there is no conception of wasting water since L.A.'s rivers are so long gone the city pipes water from the remote Sierras. In this completely altered landscape nothing remains to even suggest the possibility of an alternative to urban sprawl.

"One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds...An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise. "

Aldo Leopold, Round River: From the Journals of Aldo Leopold, 1972

Tucson is different. It changed me by opening the possibility of conceiving a past that has not been erased. In and around Tucson there are still places that have not been changed beyond memory. But it is only in truly wilderness areas that we can understand the contrast between what was and what we have created. Ironically, it is only in areas "untrammeled by man" that we understand that man is the agent of change in this great ecological drama, and learn therefore that we can change the course of history.

Sadly, most designated Wilderness areas in the U.S. are not true wilderness in the most important sense because they continue to be grazed by cows (due to "grandfathering" clauses), the most important cause of degradation. To seek out and better appreciate the contrast between the work of man (and his animals) and nature, I have begun compiling a list of true, ungrazed, wilderness areas in the contiguous U.S. states. Far and few between, organized by state, with years since last grazing in parentheses. Please email me with any suggestions or corrections.

Ungrazed Wilderness

NM

(ungrazed) part? of the Gila Wilderness in Gila National Forest

(?) White Sands National Monument

AZ

(2002-2007) Tonto National Forest, Mesa Ranger District, Sunflower Allotment

(ungrazed!) Dutchwoman Butte in Tonto National Forest

(2001- )Lower Campbell Blue Grazing Allotment, Apache Sitgreaves National Forest

OR

(2000- )Steens mountain, and (1997) Blitzen River, Burns District BLM

(1990- )Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge

(1999) Owyhee River, Vale District BLM

(? Some ungrazed, 2000- )Hells Canyon National Recreation Area, OR/ID

(1990) Warner Wetlands, Lakeview District BLM

ID

Bitterroot

Craig Wildlife

CA

California Desert Conservation Area

Peninsula Ranges Bighorn Sheep Critical Habitat, Santa Rosa National Monument (BLM) and San Bernadino National Forest

--------

Resources:

National Public Lands Grazing Campaign

Rangenet

Before and after photos from Forest Guardains

Thursday, February 21, 2008

Wednesday, February 20, 2008

What are we doing out here?

-Franklin D. Roosevelt

What are we doing out here? We come in with big yellow machinery, excavators and bulldozers and trucks, and lay waste to what we call unnatural and bad, to create a new ecosystem that we call good and natural. The alternative is accepting ecosystem "replacement" AKA ecological succession. Who can weigh all the ramifications of change to decide what is good and bad? How can we attempt to control what we don't understand? Is invasive species removal worth it?

For most of the riparian areas in the Southwest, the invasive species of focus is tamarisk:

"Tamarisk can usually out-compete native plants for water. A single, large tamarisk can transpire up to 300 gallons of water per day. In many areas where watercourses are small or intermittent and tamarisk has taken hold, it can severely limit the available water, or even dry up a water source.

Tamarisk can grow in salty soil because it can eliminate excess salt from the tips of its leaves. When the leaves are shed, this salt increases the salinity of the soil, further reducing the ability of native plants to compete. Because of its ability to spread, its hardiness, its high water consumption, and its tendency to increase the salinity of the soil around it, the tamarisk has often completely displaced native plants in wetland areas.

From a wildlife point of view, the tamarisk has little value and is usually considered detrimental to native animals. The leaves, twigs and seeds are extremely low in nutrients, and, as a result, very few insects or wildlife will use them. In one study along the lower Colorado River, tamarisk stands supported less than 1% of the winter bird life that would be found in a native plant stand. Because of the tamarisk's ability to eliminate competition and form single-species thickets, wildlife populations have dropped dramatically." Source: White Sands National Monument

So is invasive species removal worth it? It seems that, in the case of tamarisk, the best available science says yes. So we come in with the big yellow machinery.

We're not against natural change but we are against destructive change, change that impoverishes rather than re-invigorates. According to David Brower, restoration is the opposite of trying to stop the hands of time; it is an effort to keep the clock running: "The business of making something better, getting something back in shape--helping Nature heal--should make us feel good. And it will probably make our children feel better about us if we spent more time trying." David Brower Wild Earth Interview, Spring 1998.

Tuesday, February 19, 2008

Restoration History: Hoedads

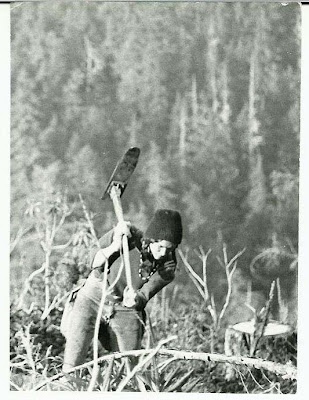

Photo courtesy of www.dechene.com

Photo courtesy of www.dechene.comThe Hoedads were an organized cooperative of tree planters, named after their tool of choice, a sort of pickax used to plant trees. Mostly college graduates, these young men and women went "back to the land" in the 1970s to care for the earth and try to live out the ideals of the the 1960's, although by the time my father was a forester in Oregon in the 1980's only "drunks and guys who couldn't make it doing anything else" were left. It was brutal labor, a job the Oregon State Employment Service lists as “the hardest physical work known to this office.., one person in fifty succeeds the three week training period.” But the scenery was fantastic, and the art, music, and poetry of the movement continues to speak to us...

...especially to those of us who follow in their revolutionary footsteps, planting trees and caring for the earth. Today, reading about the idealism of the Hoedads, it is tempting to romanticize their work in comparison with our own. For example, both men and women Hoedads commonly worked shirtless, while today we rarely work shirtless and there aren't really many women on the crew anyway.

But, reading further history reveals trade-offs even in paradise. The Hoedads were exposed to sprayed herbicides and pesticides, while today we avoid using most poisonous chemicals (except petroleum products). Our work today, like the Hoedad's, is a product of our times. We drive trucks and eat processed food and doubt whether we can make a real difference, while the Hoedads confronted prejudice, exploitation, and chemical toxins with the fresh idealism of the 1960's. 40 years later it can be hard to see if much progress has been made (there are still so many forests and riparian areas to re-plant!), but perhaps the important fact is what has stayed the same: the dedication, hard work, and, yes, idealism to try to make a positive difference on the earth.

"God almighty! Why am I here, saying this, and not there, and not doing, and making the forest?"

Please read this great verse poem by Richard Bear eulogizing the Hoedads.

-

How to use a hoedad.

Monday, February 18, 2008

The Day After Tomorrow

The movie "The Day After Tomorrow" is about the end of the world, and, unexpectedly, the cinematography is fairly good. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed seeing Los Angeles destroyed. New York is another matter: NY is destroyed every other weekend at the box office, and I've never lived there anyway, but I have lived near LA and I now believe that every good movie should destroy something important in your life.

Plus, the scientific side of the story was thought-provoking. Catastrophic (saltational) climate change can't be ruled out based on our present state of knowledge. The fossil record isn't precise enough to determine if past climate changes happened in 5, 50, or 500 hundred years. Also, the current level of Co2 is unprecedented for at least the last 400,000 years (the limit of our ice core data) and the rate of increase is likely unique in the entire history of the planet. We simply don't know enough from past experience to accurately anticipate how this is all going to play out.

The IPCC has issued a series of scenarios with likely average temperature increases, but a thorough understanding of the problems inherent in such models calls into question the precision of these averages. The most commonly cited average gives increases of of 2-6C over the next 100 years. But all of the models they currently use are inherently gradualist models (more on this below). One could be a skeptic whether these models are accurate at all, but their (retrograde) prediction of the cooling associated with the Mt. Pinatubo eruption convinced many of their validity. It is edifying to note the maturation of models that originally didn't even take into account atmospheric dust; this is certainly a new science and many problems remain to be solved, particularly the response of vegetation to increased CO2. (CF. McNaughton & Jarvis. Effects of spatial scale on stomatal control of transpiration. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 54, 279-301). There is a definite possibility that other, as yet undetermined, variables could play a significant role in future climate change.

But the problem with relying on IPCC averages as outer limits of possible climate changes goes deeper than possible 'out of left field' variables. A recent effort using contemporary day-to-day "matrix" models of weather (e.g. the kind that are used to predict the path of hurricanes) to predict long term climate change yielded slightly higher averages (up to 11C) than the IPCC,. But the most important result was buried in the calculation of these averages. It turns out that the researchers, like many other modelers, ran their simulation thousands of times and only averaged the results that seemed reasonable. A significant proportion of the models "crashed" to negative or positive infinity temperature. Obviously, these results could not be averaged with the simulations that "worked", but they instead point to the instability inherent in these equations.

The climate change models and the way they are interpreted are inherently biased toward gradualist results, but the real danger of climate change is unpredictability. A perfect storm probably won't jump-start a renewed ice age in a manner of days, as in The Day After Tomorrow, but more humble respect for the mysterious potentialities of nature may be wise. The hubris of those who calculate the economic cost of the IPCC predicted change are one example of what can go wrong in a cost-benefit analysis that doesn't factor in the possibility of catastrophes. Attaching specific temperatures to the future climate of the earth is an important undertaking, but it is not a perfect science. Nothing is.

Sunday, February 17, 2008

3 Fairy Tales

One morning when the sky was already full of sunlight, a young girl woke up and looked out the window at the beautiful rolling country and the beautiful shimmering river. She was a beautiful princess and she rode out with her prince riding in their kingdom over gently rolling hills of sagebrush until they came to the smooth river edged in channels within channels, braided like the hair of the princess. They rode slowly under giant trees along the bank of the beautiful river and were greeted heartily by everyone they met. So they wandered long over the land, pausing often to appreciate the beauty of each place; unique, humble, magnificent. It seemed they rode through a stained-glass universe in which every scene was perfectly arranged and proportioned. The soaring eagles, the tall grass, the limitless blue sky. their own youth and health. The day was so full of wonder and love that any conception of past or future disappeared.

In this enchanted state of mind they sat down to picnic on a sun-dappled river bank, soft, with high grass all around and trees shaded where the river came in to a deep pool and where it went out, so that only their own illuminated moment of deep and calm water existed. They lay there for a long time looking at the water until, later, the prince caught a small fish. It was fat and full of eggs but they ate it anyway. Each egg was a jewel of juice in their mouths, and when they ate the flesh of the fish their saw rainbows dancing in the water. The colors swirled around them and their blood became rainbows dancing in their hearts and they fancied they knew what it must feel like to be a fish.

As I said, they were enchanted. And so when they began to wonder where the water came from or where it went, their thoughts were not the usual human words and ideas, but rather, the slippery and adaptable thoughts of creatures who accept the water as eternal and incompressible...as life itself seemed. Where was there room for more? But still the river flowed. Was the water pushing up on the one side of the pool, or pulling away on the other side? How could the water on the one side know to move out of the way of the water on the other....or, alternately, how could the water on the other side know it needed to flow down and take the place of the departing water on the first side?

With these thoughts swimming in their minds it need scarcely be mentioned the need they felt to depart their human clothing and slip into the cool clear pool to experience their own smooth bodies, so smooth they forgot to breathe, so fishlike they forgot all about being a princess and a prince, and were finally fish with rainbows in their hearts, perfectly enfolded in the flow. Every effortless gesture transformed and became movement, a perfect fit in the perfect stained-glass world.

And that is how fish came to live in the water. But, oh reader, don't worry where that fish they ate came from... it came from their own minds, of course. From their own minds.

--------------------

--------------------

Torrid

There was a small town between the dry mountains and the sea, where a dark-eyed people lived peacefully and slowly. Slowly because they lived in a hot desert where the sun stood still every day, high in the sky, so they stayed still in the shade, taking the siesta. Every summer the heat came wavering down out of the barehills and the sun shown so mercilessly it baked the ground and their humble dwellings and their skin until everything became sunbrown leather and they looked out of sunbrown leather faces at their sunbrown leather houses. The people were healthy and happy because the sea was full of fish and it wasn't such a bad place in the winter, anyway.

But one year the winter didn't come. Or, it came, but it was as hot as the summer and the dark-eyed people peered out from faces of sunburnt leather and asked one another, if the winter brings no relief from the heat, what will happen come summer? They sheltered in the shadows fanning themselves and waited, as they did in the summer, for the winter, but since it was already winter they didn't know what they waited for. Every shimmering-hot day was hotter than the last, and they spoke in low voices as if they were suffocating, holding their breath with nothing to hold it for

Spring was still hotter, hotter than any summer they could ever remember before. The people grew afraid and looked with their dark eyes out of the sunbaked faces at their sunbaked town, at the dry plants and dead trees and the animals panting weakly. Only the fish were healthy and happy. The heat was incredible. It was impossible to lie down to sleep, impossible to move. The wind, when it did come out of the stifling hills, was like the blast of air from an oven. Nothing could stand the heat, rubber melted, paint peeled, everything dried out and turned to dust.

The sunblistered people camped along the beach, swimming to keep cool. They stuck poles in the surf and hung hammocks there to sleep, and swam and fished all day, and forgot about their former homes. Fires started spontaneously in the town, the land was so bright and bare it hurt to look at it, and it was impossible to walk on it.

Then summer came. When the sun rose over the water the sky exploded with a kind of oppressive brilliance, a red-hot wall of fire that seared everything it touched. The people gulped a burning breath and dived under the waves and held their breath as long as they could, and when they couldn't hold it anymore they quickly gulped another, and dived again to avoid the torrid surface. They kept breathing in gulps and eating fish and they were healthy and happy and it wasn't such a bad life in the summer, anyway... and today we call them dolphins and wonder why they don't build houses or sleep in beds....

The Graph

The American West was colonized by Anglos during some of the wettest periods in the last 1,000 years, according to the February 2008 National Geographic. These abnormally wet years are depicted as mountains surrounded by valleys of drought in a graph of Colorado River Streamflow reconstructed using University of Arizona Lab of Tree Ring Research. The highlight denotes a 60-year drought that was consistently as severe or worse than the current (1998-2008) drought. Judging from the jagged oscillations of this graph, such droughts may be a regular and normal occurrence, although not for our modern water-spoiled civilization.

The American West was colonized by Anglos during some of the wettest periods in the last 1,000 years, according to the February 2008 National Geographic. These abnormally wet years are depicted as mountains surrounded by valleys of drought in a graph of Colorado River Streamflow reconstructed using University of Arizona Lab of Tree Ring Research. The highlight denotes a 60-year drought that was consistently as severe or worse than the current (1998-2008) drought. Judging from the jagged oscillations of this graph, such droughts may be a regular and normal occurrence, although not for our modern water-spoiled civilization.See also National Geographic News, "U.S. Drought Could Be Start of New Dust Bowl"

Saturday, February 16, 2008

My Life in the Newspapers

I'd like to comment on some of these articles, grouping them into three major subjects: the "toilet-to-tap" furor in Tucson, fighting invasive species, and tracking Jaguars.

Friday, February 15, 2008

I. Toilet to Tap

Americans are different from most people on the planet. We have indoor plumbing and can turn on fresh, drinkable water any time we want. But the combination of the two may be our undoing. We don't pay a quarter of our salaries and spend hours waiting in line to get potable water, and maybe because of that we have abused our privilege. Now that the rivers are drying up in the West, cities are looking to new sources of fresh water. But where?

Ironically, "San Diego has both a water-supply and a water-disposal problem." Why not use the water in need of disposal as a new supply? Maybe because the slogan is "Toilet to tap"?? Sustainability advocates in Tucson (myself included), recently tried to pass a ballot initiative (Prop.200) with just such a slogan. Our reasoning: if Tucson doesn't want "toilet-to-tap" we had better start limiting growth now, before that's our only option. The opponents of the measure (ie proponents of growth such as developers) argued that Tucson would never need to divert wastewater into drinking water. But, just weeks after Prop.200 went down in flames (after mafia-style threats from the developers), amid reports of more drought, the Tucson papers began suggesting that perhaps Tucson really does need to start looking into the idea, after all.

Of course, all water is recycled eventually. Tucson is currently "recharging" its aquifer with wastewater. As the wastewater seeps through hundreds of feet of sand the hydrologists claim it will be cleaned enough to draw back up a well for drinking water. Las Vegas uses an even more direct filtration approach: "Los Vegas alone discharges roughly 60 billion gallons of wastewater a year some miles upstream of its own water intake -- a feat of urban engineering that would seem to prove that most of what happens in Vegas really does stay there."

All of which just points up the rationale San Diego used in its (failed) attempt to utilize wastewater: "We can have a lot more monitoring and control if we oversee our own reclamation than if we're relying on a river with a billion gallons of recharge [in the Colorado River] from other sources every day." Bruce Reznik, executive director of San Diego Coastkeeper. Just as no place is truly a wilderness "untrammeled by man" anymore, so too no source of "clear mountain springwater" is truly without some contamination, e.g. some "clear mountain streams" high in Colorado have enough man-made chemical estrogen mimics to feminize fish.

Friederici, a journalism professor, has written a great article that touches on some very deep issues in the interplay of science, technology, and society; E.g. the trust ordinary citizens place in their own biased perceptions versus the scientific analysis of professionals. The article suggests that that "perceptual shortfalls" in ordinary citizens might in fact be a reasonable, precautionary reaction to the belated discovery of the harms of rGBH in milk and endocrine disruptors in plastics. Without the ability to "see" contaminants that affect them ordinary people may have to rely on the history (story, narrative) of their water to determine quality rather than the quantitation (appeal to authority) of scientists.

-

A simple solution the article overlooked: *abandoning our water-treatment infrastructure* and giving in to the bottled water craze. This water crisis is caused by the average American household sending 150 gallons of fresh, drinkable water down the drain every day. If we could use untreated or sub-potable treated water for most domestic needs and bottled water for drinking and eating we would eliminate the source of the dilemma: overconsumption. However, if, in the end, the punishment for being spoiled Americans is drinking our own toilet water, perhaps there is some justice in this crazy universe after all.

Thursday, February 14, 2008

II. The War on Invasive Species

...and A dustup over weed control. The BLM's plans to spray nearly a million acres with herbicides have some environmentalists fuming, but many biologists and land managers welcome the policy. WESTERN ROUNDUP - September 3, 2007 by Eve Rickert

...and Beetle Warfare. What happens when an exotic bug is brought in to fight an exotic weed?

Invasive species are a huge problem in the Southwest and these articles highlight a number of the major culprits: Buffelgrass, Lovegrass, Cheatgrass, and Tamarisk. These interlopers cause upwards of $120 billion dollars of damage a year and are reason almost half of the species on the Endangered Species List are endangered (Pimentel, 2004).

In the Sonoran desert around Tucson, particularly the front range of the Santa Catalinas, I have witnessed the utter devastation that a climax-changing invasive can bring to native ecosystems. Where Buffelgrass grows it chokes out native Saguaros, and worse still, creates conditions perfect for wildfires. Since the grass is adapted to fire and the native Sonoran plants are not, this feedback cycle creates exponential growth of Buffelgrass at the expense of the former ecosystem.

I have also been witness to the seeming-futility of manual removal of Buffelgrass as a member of the Tucson chapter of the Arizona Native Plant Society. But what are the alternatives? The second article points up the contradictions of spraying herbicides to try to save the native ecosystem in a kind of logic akin to the Vietnam war's "It became necessary to destroy the village in order to save it." There are certainly many benefits to chemical treatments, and it is not clear how to interpret the Precautionary Principle in this case of "damned-if-you-do, damn't-if-you-don't".

I am again confronted with the enormity and seeming-futility of manual removal in my work with Forest Guardians removing Tamarisk, a large tree that dries up rivers throughout the West, choking the native riparian ecosystem. We exhaust ourselves pulling up every piece of a plant that can propogate from bits of root just a few inches long. But what are the alternatives? I for one am personally glad Forest Guardians doesn't use chemical treatment, and there are many indications that chemicals, especially one-time applications, are not effective, either. The third and last article in this comment suggest the use of another invasive species. Invasive species are, by definition, species that have escaped the natural checks and balances of their native ecosystem. So why no bring some of those naturally evolved checks to give the Tamarisk a taste of their own medicine? But Jim Matison of Forest Guardians explains: 'Two species do not an ecosystem make.' According to Jim, introducing another non-native is just another example of our hubris replaying the same old mistake; believing that Science can predict all possible interactions and ramifications. In other words, playing God.

But, maybe, aren't we already playing at judge and jury when we decide which ecosystem (Buffelgrass vs. Sonoran, Tamarisk vs. Riparian) is good and which is bad, which plant lives and which plant dies?

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

III. Tracking Jaguars

The Jaguar is what is known as "charismatic megafauna" in conservation circles. This animal prowled the mountains overlooking Tucson less than 100 years ago, before it was exterminated by government predator control efforts. Today, its natural migration back into the Southwest is being hailed as a confirmation of improving ecosystems and attitudes. The network of wilderness preserves and conservation practices have begun to recreate the habitat these keystone species need. But they need more than land: they also need human understanding. Indeed, we would not even know about their return if not for the enlightened response of certain ranchers who chose to photograph, rather than shoot, these "illegal aliens".

The Border Patrol has also weighed in on the cat's fate, forging ahead and building a wall along the border without any kind of environmental impact research. The crisis of (human) migration across the border is dire and the idea of building a wall is understandably attractive, but many believe it will end up more effectively blocking wildlife migration than human.

Voas goes beyond merely reporting the facts in this article to unearth the complicated melange-a-trois politics between the conservationists, the ranchers, and the Border Patrol. If conservationists are going to save the Jaguar in the American Southwest, it may mean working, and yes, even accommodating, "multiple use". For example, most conservation organizations would like to expand wilderness areas, or develop other restrictions on land use such as Critical Habitat Designation (CHD) for the Jaguar. While these conservation "gold standards" are arguably best for the recovery of the Jaguar they may end up being "counterproductive by imposing limits on land usage, including grazing....[which would] enrage ranchers."

According to Emil McCain, a biologist for the Borderlands Jaguar Detection Project, "A CHD is going to do far more harm than good for habitat...It makes enemies of the people you need to rely on." Michael Robinson, of the local conservation group Center for Biological Diversity is undeterred: "Our stance on grazing is that it should not preclude the presence of any native species, that it should not pollute waterways, and it should not cost the public any money. If the livestock industry is going to step up and meet those standards, it's OK with us."

But making such demands risks offending the owners of the very land Jaguars need. This is the old paradox of the Endangered Species Act, a paradox that is especially relevant in the almost lawless borderlands: CHD might encourage ranchers to kill an endangered animal rather than report it and face more rigorous regulation of their land or grazing allotment.

A similar dilemma for conservationists concerns the Border Patrol (BP) and the wall: whether to work with the BP and suffer the slings and arrows of their outrageous ecosystem disruptions, or to takes arms against what seems to be a rising sea of misplaced government intervention and lose any hope of compromise. As it stands the BP are cooperating with conservationists by maintaining and sharing open records of Jaguar sightings. Their cameras may play an important role in the badly-needed work determining Jaguar migration routes.

Of course, conservation organizations like the Sky Island Alliance, while working with all concerned parties, are also pursuing their own independent monitoring program. As a graduate of their Wildlife Tracking program I have helped monitor charismatic megafauna throughout the Southwest, and remain hopeful that the Jaguar will bring the different human tribes together, rather than tear us apart...

Tuesday, February 12, 2008

Tucson

0.

Even the great amoeba cities, clutching each other, skewered on their endless myopic highways, shrink in comparison to the vastness of the landscape in the West. These desert cities, surmounted and circumscribed by wondrous mountains wink small and lonely in the dark night, lost in all-encompassing wilderness. We live that we may be worthy of this landscape.

I.

Tucson, loud city of impolite dogs and cars, planted with inedible fruit and painted with bland colors, at least you are ringed by mountains for every mood. The humble-yet-graceful hump of the Rincons, huge on the Eastern horizon. The jagged charismatic physiognomy of the Santa Catalinas looming in the North, dominant, heroic, common. The austerely lush, picturesque Tucson mountains, dry yet creative, flowering along the West. And finally the distant-beyond-estimation Santa Ritas, spooky at a distance, foreign and strange and Southerly.

II.

Santa fe, quiet city of streamlined roads twisting past close-set fences...[unfinished]

Hiking Barefoot?

"The Barefoot Hiker" A Book About Bare Feet

by Richard Frazine, BD [Bachelor of Divinity?]

1993, Ten-Speed Press, ISBN: 0-89815-525-8

Read the book. Join the club.

This is an excellent and well-written book full of irreverent spunk and practical advice for hikers who habitually go barefoot. It is also an interesting addition to my "What would caveman do" bookshelf (see: Anopsology and my analysis). But, this book is written by Easterners, and I must humbly take exception to the application of their advice to the west, particularly Tucson.

The authors would sore regret hazarding a single barefoot footfall, let alone an entire cavalcade of such vulnerable events, in the Sonoran Desert, a Desert incomparably well-equipped to puncture the inflated expectations of innocent trespassers. The rapacious wit and perspicacious criticism embodied in the hard reality of the Sonoran desert would soon render the author's philosophy moot as he became a human dumpling skewered on the spines of cholla, saguaro, fish hook, and porcupine cactus, not to mention the infinitely small, sharp, and numerous "glochids" of the prickly pear.

The idea that humans are fit to live in the environment uncouth and unshod is an admirable one, an idea dating back perhaps to Genesis and the Garden of Eden. But the beauty of wilderness, especially Sonoran desert wilderness, bursts such hubristic bubbles and skewers such dainty pedagogy. Aristotle's peripatetic circumlocutions aside, this shit is sharp. To take humble pride in the profligate-armed Saguaro, to know that we are outmatched and vulnerable at his side, is to know the true reality of wilderness: not unadorned freedom to trample as we wish, but careful respect for all creatures great and sharp, and a willingness to adapt our footprint to the landscape we inhabit.

Friday, February 08, 2008

Thoughts on Ecology by Begon, Harper, and Townsend

Not Just Drops of Goo

The smallest idividual droplets of life are fundamentally different from one another, as opposed to physics or chemistry where the fundamental parts are interchangable. There are at least 100 million distinct types of droplets (excluding viruses, proteins, and undiscovered types), each with its own inherent and combinatorial talents. These special abilities are written out in the droplets' DNA, so that every tiny snippet in my body is fundamental to me and contains the possibility of me.

People and animals and plants (and indeed all life) were not put here randomly-- we each have a reason. Sometimes that reason is just because here is near where our parents happened to live. Everywhere in the world children live near their parents. But if you go live on an island you would become different. The 'you' that you are can't go live on an island without becoming a different 'you'. The 'you' that you are is based on where you are. And so all life forms are different in different places. Yet Darwin teaches that they are the same stuff, from the same parents. We are all brothers and sisters, made of the same protoplasmic ooze.

This, then, is the tension in biology: we are all fundamentally the same goo but we are all fundamentally different goo. "There are no differences but differing degrees of difference and non-difference." CF. "The Influence of Darwinism of Philosophy", 1909 John Dewey.

"All species are absent from almost everywhere"

But: not everything important is alive - rocks, sunlight, clouds, motorcycles. All of these things push and shove on each other and on life. So to study life we have to study all of these things. Life itself is constantly bouncing against itself and, in fact, this is what makes life alive. What does this constant bouncing need to keep going? It is many things in many places; different things in different places. It is often a balancing act between hot and cold, between light and dark...

Everything in nature is good at something; balancing, breathing, sweating, slurping. But the sad wisdom Darwin teaches is that we only know we were good at something in the past - who knows if we will fit in the present or find a place in the future? There is evidence all around us of stranded animals and plants and people who stayed while the world changed around them. The past is no garuntee of the future.

The fundamental questions of Ecology: Why does this thing live here (why am I here) and Why do different things live in different places (Why am I different)?